I have been working in the climate field for over 25 years, and it is only in recent years that I have learned more about the history of Earth. It has been a fun journey because Earth has some great stories to share.

Despite years of little progress across nations to address our climate change imperative, I still passionately believe that humans will switch to renewable energy systems and restorative agricultural and land use systems that address the climate change challenge. After all, our survival instinct is strong, and while we may not excel at being a proactive species, we are certainly good at being reactive. However, the more I learn about feedback loops, the more the delays in climate action implementation cause me anxiety and undermine my faith and hope in humanity. These feedback loops create a risk that even if we get our act together and finally act on our climate imperative, that won’t be enough to protect us from average temperature increases that can create untold misery.

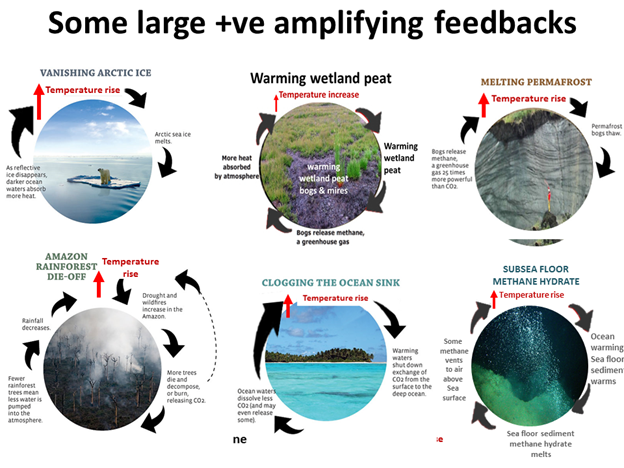

So, let’s dig into a few feedback loops that we should be very concerned about. Reducing the risks of triggering increases in these feedback loops is one of the reasons why limiting our average temperature increase to under 1.5 degrees C temperature is so critical. Going beyond that sets us up to trigger a runaway on the following feedback loops.

Let’s look at the feedback loop we know the most about: shrinking arctic ice. In the Northern hemisphere, most of the arctic ice is over the sea, whereas in Antarctica, the ice is on top of the Antarctic land mass. When arctic ice melts over the sea, the surface exposed to the sun changes from a white snowy surface to a dark ocean, decreasing its albedo drastically. The darker ocean absorbs more heat, further increasing arctic ice melt, and so on. On the other hand, melting permafrost risks releasing an unknown amount of methane – a potent greenhouse gas. Crucially, keep in mind that the climate models informing our future do not include the release of methane from permafrost because, honestly, we don’t know how much is stored there. So even if we advance needed changes, it might be too little, too late as the feedback loop kicks in.

In contrast, the feedback loops stemming from deforestation and forest fires are straightforward. Deforestation removes carbon sinks, and forest fires release vast amounts of CO₂ into the atmosphere. While new vegetative growth will occur, it will take many years for the trees to mature and the forest to become a carbon sink again. Mature forests are far better at carbon sequestration than younger, fast-growing forests.

The ocean also acts as a carbon sink, absorbing almost 50% of the CO₂ that we release into the atmosphere. Yet as the ocean temperature warms, it absorbs less and less CO₂, thereby removing a carbon sink we greatly need. Even if we ignore the ocean as a carbon sink, increased CO₂ levels in the ocean cause ocean acidification and lowers the pH of the ocean. This critically impacts marine organisms’ ability to make their shells, affecting all coral reefs, which in addition to being one of the most beautiful and magical habitats on the Earth, also serve as the nurseries for the ocean’s fish. Ocean acidification will have significant consequences, as more than 1 billion people rely on fish as their primary protein source.

The least well-known feedback loop is the release of methane from the ocean floor. Without knowing specifics, we know that immense amounts of methane are trapped in the sediments beneath the sea floor, frozen into a form of water-ice called methane hydrate. As the ocean warms, we risk warming the ocean floor so much that it starts to release the methane stored there and creates ocean anoxia (low oxygen levels) which is a terrible habitat for fish but a great home for algae.

Despite these concerns, I remain optimistic that humanity will get our act together while admitting these feedback loops truly frighten me. We need to accelerate the global shift from dirty fossil fuels exacerbating climate change to renewables so we can run our lives and economies without destroying our planet. If global temperatures continue rising, some of these feedback loops could spiral beyond our ability to reverse the warming.

By Gaby Kalapos, Executive Director